Given some of the uncertainty surrounding mental health diagnoses previously described, it is perhaps inevitable that getting a clear picture of the prevalence of mental health challenges in Cumberland is not easy. However a range of data can be used to give an indication of relevant patterns.

Primary care data

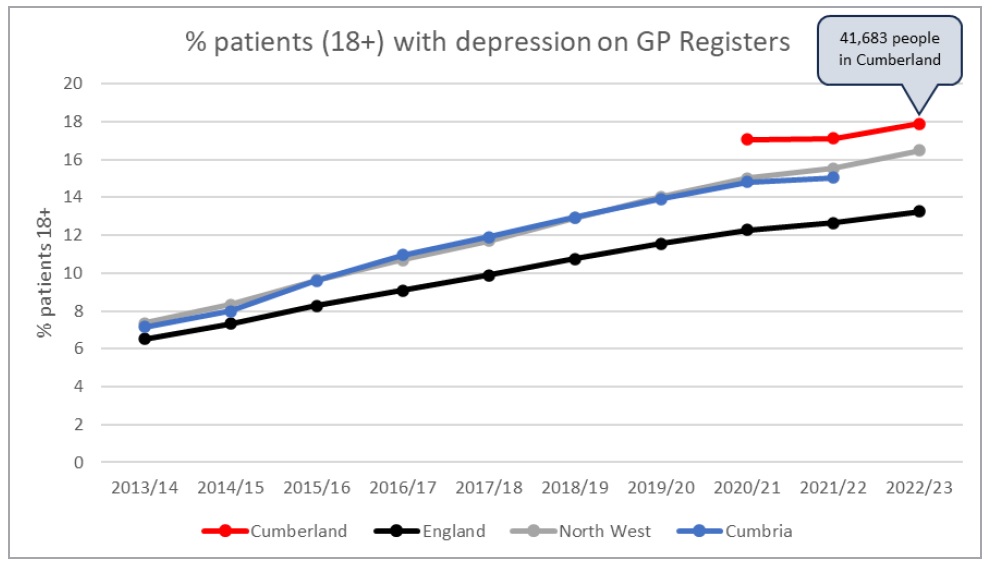

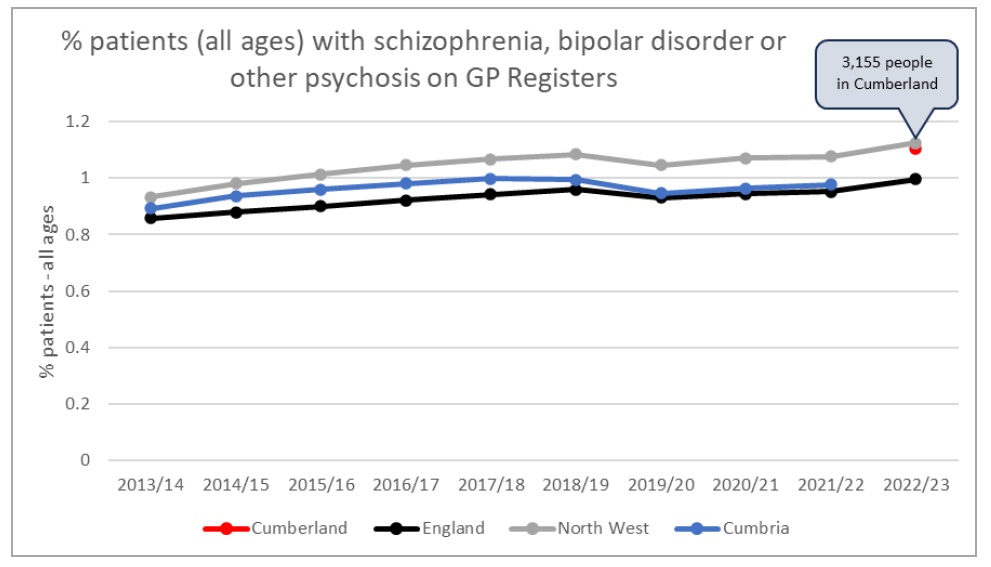

Data from GP Registers paints a dramatic picture of changes to some categories of mental health demand. Across the whole of England, the number of people being recorded by GPs as having a diagnosis of depression has nearly doubled in 10 years. While some of this may reflect improved recording and reporting, it is stark that in 2022/3, over 40,000 people in Cumberland – 18% of the adult population – was recorded as having depression, a rate that is over a third higher than the England average (Figure 1). This rising trend is less dramatic with some other mental health disorders (Figure 2) but even here there has been a 15-20% rise in 10 years, with over 3,000 people in Cumberland recorded as being diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other psychotic disorder, around 10% higher than the England average.

Figure 1: Rising rates of recorded depression over the last ten years

Figure 2: Trends in selected mental health disorders

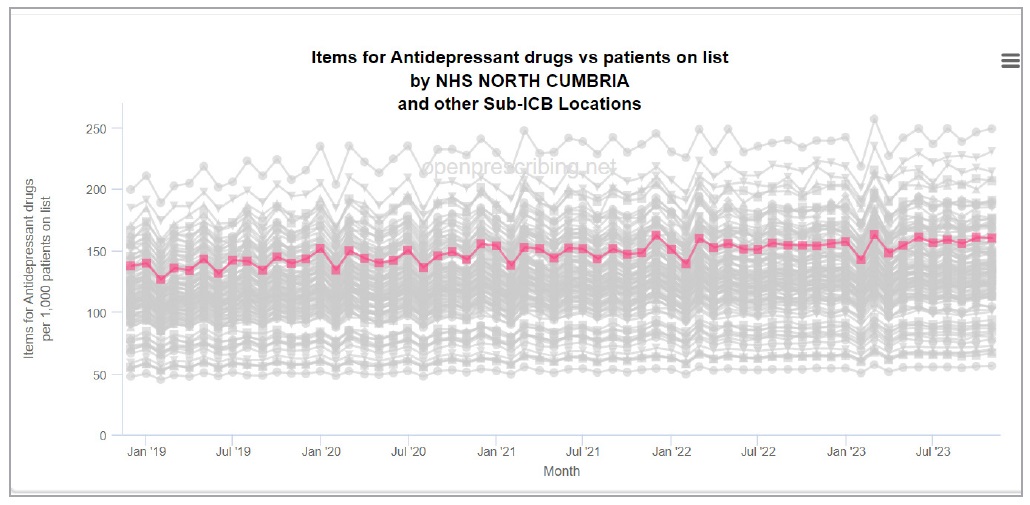

These data can be valuably cross-referenced to prescribing data (OpenPrescribing.net, 2024). In NHS North Cumbria, which covers the vast majority of Cumberland but also includes the former Eden District in Westmorland and Furness, antidepressant (British National Formulary section 4.3) prescribing was around 160 items per 1,000 patients in November 2023 (Figure 3); this is again a third higher than the England average of 120 items per 1,000 patients. Figure 3 also show the increase in prescribing over time: the England average in December 2018 was only 100 items per 1,000 patients, indicating a 20% rise in prescribing over the last five years. And this prescribing does not come cheaply; in the year to November 2023, in NHS North Cumbria the 622,078 items prescribed under the category of antidepressants cost £1,391,345.

Figure 3: Antidepressant prescribing over time (North Cumbria figures highlighted)

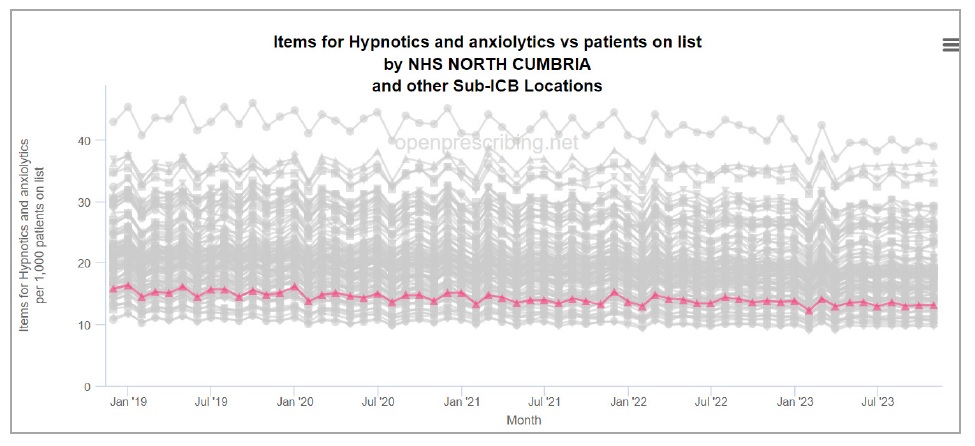

The prescribing picture is slightly different for other mental health conditions. Prescribing of hypnotics and anxiolytics (anti-anxiety drugs – BNF Section 4.1) has been falling in recent years, and is low in North Cumbria compared to the national average, at about three quarters of the national rate (Figure 4). Despite that, the year to November 2023 still saw 53,041 items prescribed in this category, at a total cost of £448,668.

Figure 4: Prescribing of anti-anxiety drugs over time (North Cumbria figures highlighted)

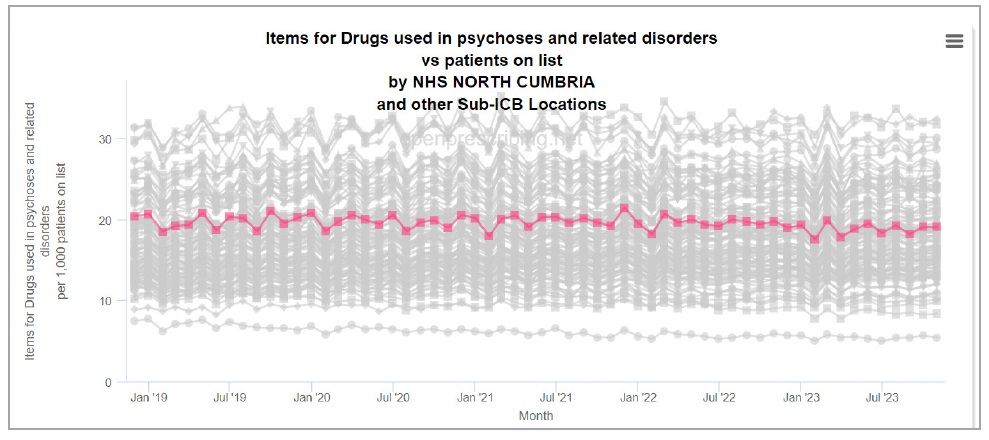

The picture for anti-psychotics (BNF section 4.2) has been quite stationary for the last five years (Figure 5) at around 10% higher in North Cumbria than the national average – relatively consistent with the GP Register data shown in Figure 2. In the year to November 2023, there were 74,866 such items prescribed at a total cost of £887,301.

Figure 5: Antipsychotic prescribing over time (North Cumbria figures highlighted)

In total, the cost of primary care prescribing across these three categories of mental health medications in North Cumbria in the year to November 2023 was £2,727,315. Note that this is only the prescribing carried out in primary care – it does not include prescribing done in secondary care or specialist mental health services.

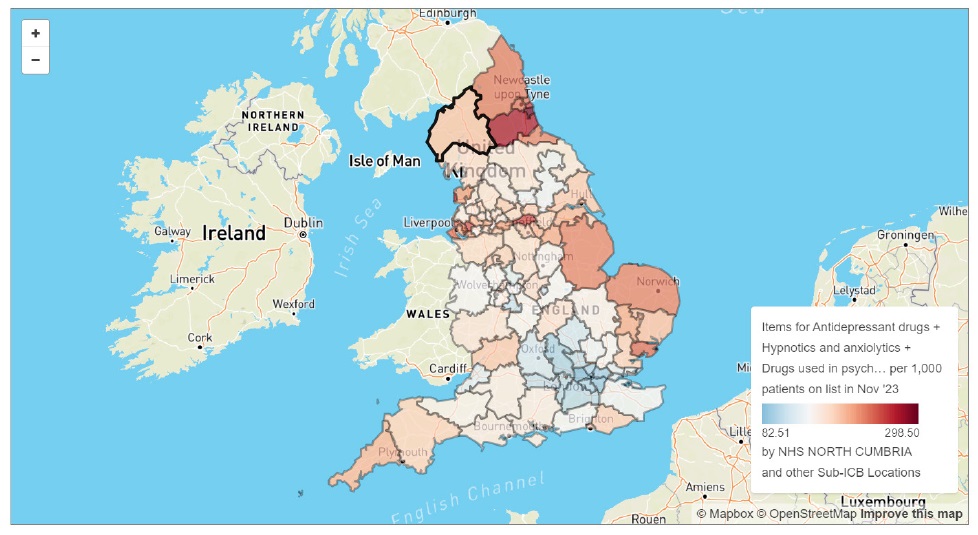

As an important side-note, prescribing of these drugs show a predictable pattern across the country: it is higher in northern and coastal communities and areas of higher socio-economic deprivation, as can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Prescribing of mental health medications by ICB sub-region (North Cumbria highlighted)

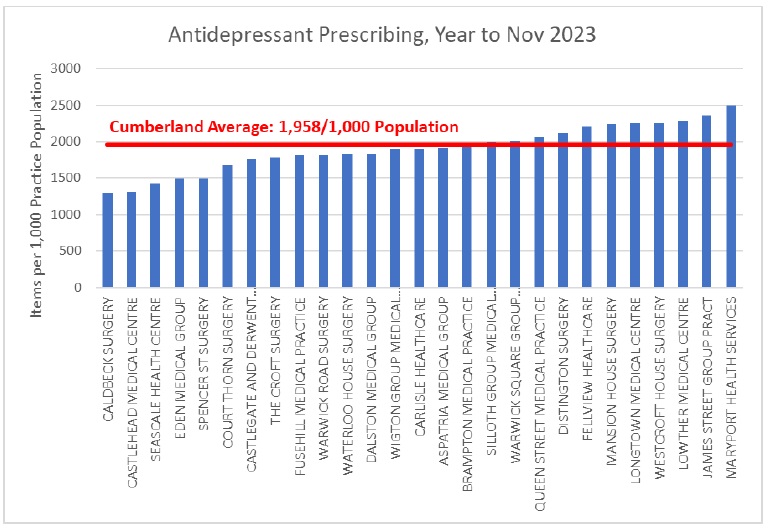

There is also considerable variation within Cumberland, as shown in the breakdown by GP Practice in Figure 7, with the highest prescribing practice issuing nearly twice as many items per patient as the lowest.

Figure 7: Antidepressant prescribing by Practice

Specialist mental health services

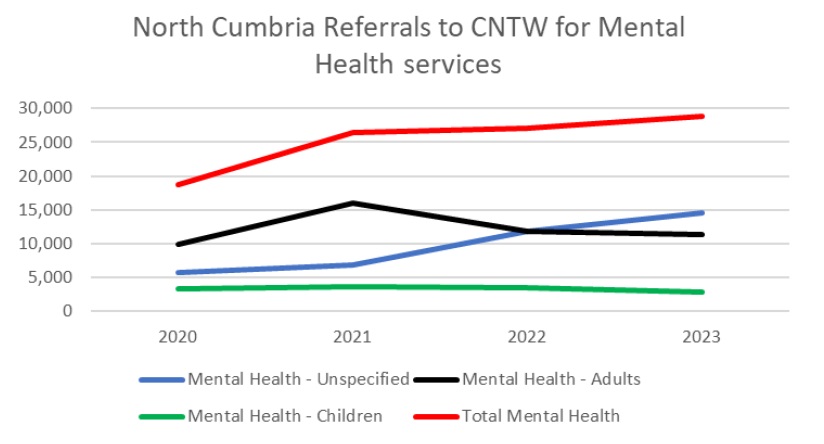

In Cumberland, specialist mental health services are primarily provided by Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne & Wear NHS Foundation Trust (CNTW). The number of referrals to CNTW has increased by more than 50% over the last three years alone (Figure 8), putting huge and unsustainable pressure on the system.

Figure 8: North Cumbria referrals to specialist mental health services

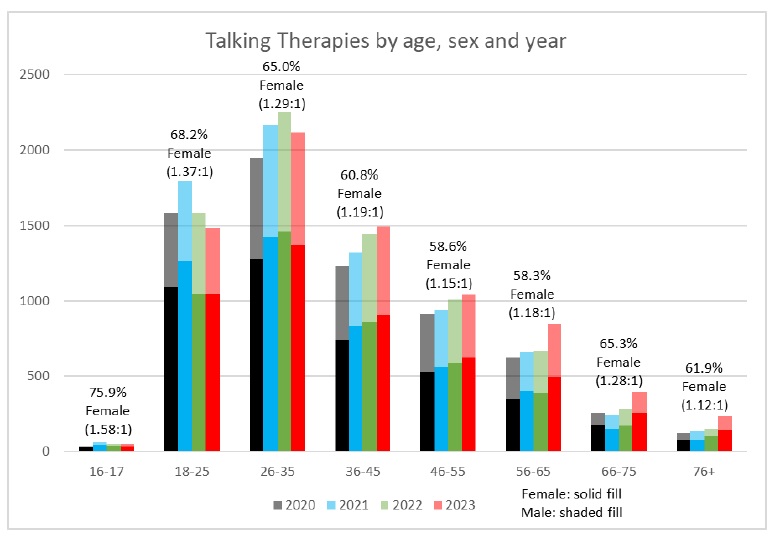

Within specialist mental health services, the number of people taking up talking therapies (mainly cognitive behavioural therapy) has increased by around 15% since 2020, rising from 6,730 to 7,706 in 2023. Figure 9 shows how the use of talking therapies is highest in younger age groups, progressively decreasing after the age of 35; it also illustrates how this type of intervention is predominantly taken up by women – though this discrepancy reduces with age until middle age, after which it rises again.

Figure 9: Talking therapies by age, sex and year

Demand on services means that waiting times for talking therapies in North Cumbria are challenging. While the vast majority of referrals (4,985/5,050 in 2022/3) are seen for a first time within 28 days, with an average waiting time of 5.8 days, the time between first and second appointments is considerably longer – an average of 44.9 days, with 415 people waiting more than 90 days for a second appointment. This matters because these therapies can be highly successful, with the majority of people seeing clinically and socially significant improvements across a range of mental health and wellbeing scores and very high levels of satisfaction with services.

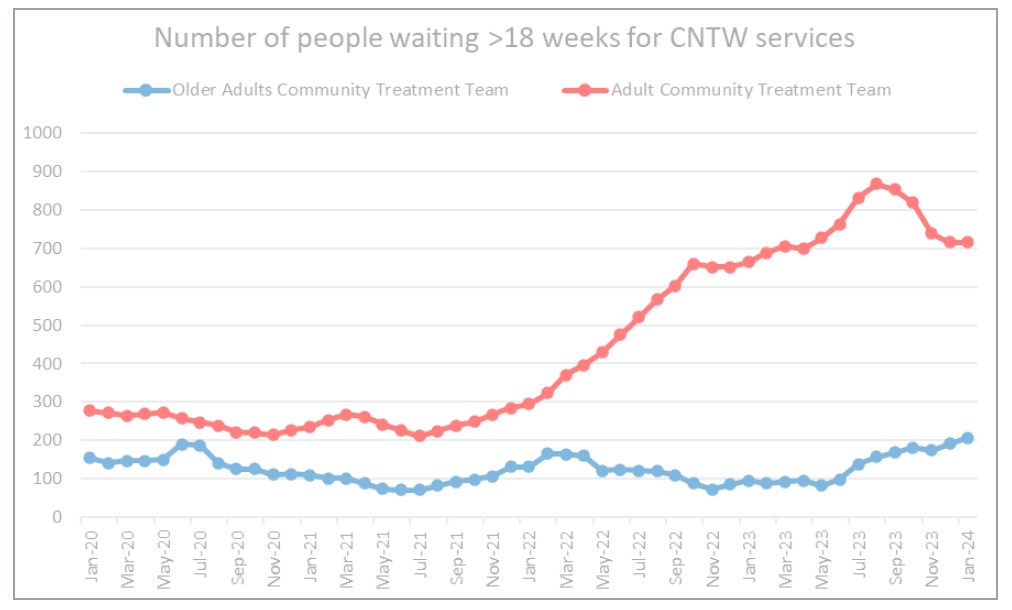

In wider specialist mental health services it is now far from unusual to wait for more than 18 weeks before receiving services. Figure 10 shows the rapid rise in waiting times for general adult community mental health services since 2021; the comparison with older adults services is instructive as the latter are mainly driven by dementia diagnoses, which are not so susceptible to the socio-cultural pressures described in Chapter 1.

Figure 10: Waiting times for community mental health services

Consequences of poor mental health and wellbeing

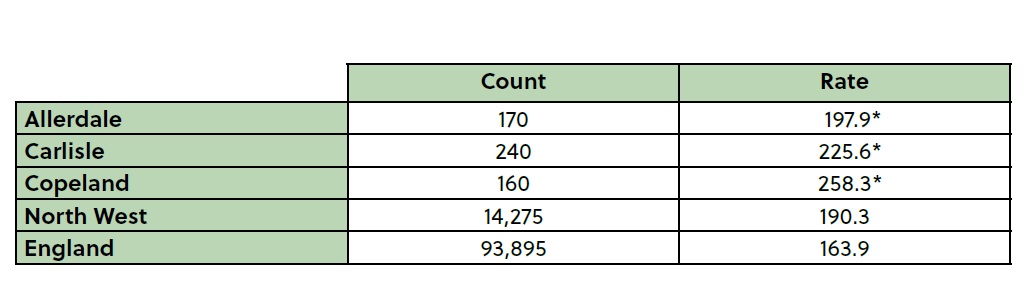

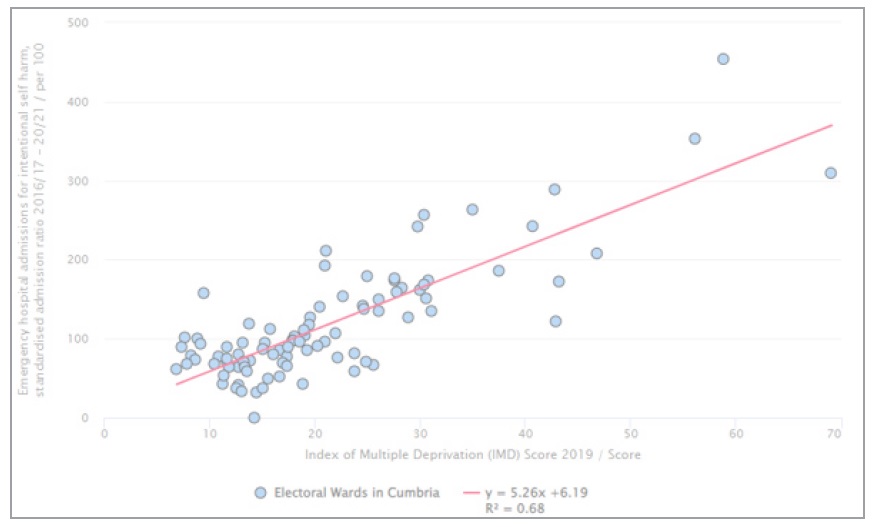

As noted in Chapter 1, there are several health-related behaviours that can usefully be seen not just as separate phenomena but as symptoms of a broader mental distress – not themselves mental health problems, but consequences of them. These include self harm, addictions, and suicide. And across all three, Cumberland has significantly high rates. Emergency admissions for intentional self-harm are significantly above the England average in all three of Cumberland’s former Districts, as shown in Figure 11, and follow a close relationship with deprivation, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11: Emergency hospital admissions for intentional self-harm (Directly Standardised Rate per 100,000), 2021/22. * Statistically significantly worse than England average, p<0.05

Figure 12: The relationship between self-harm and deprivation

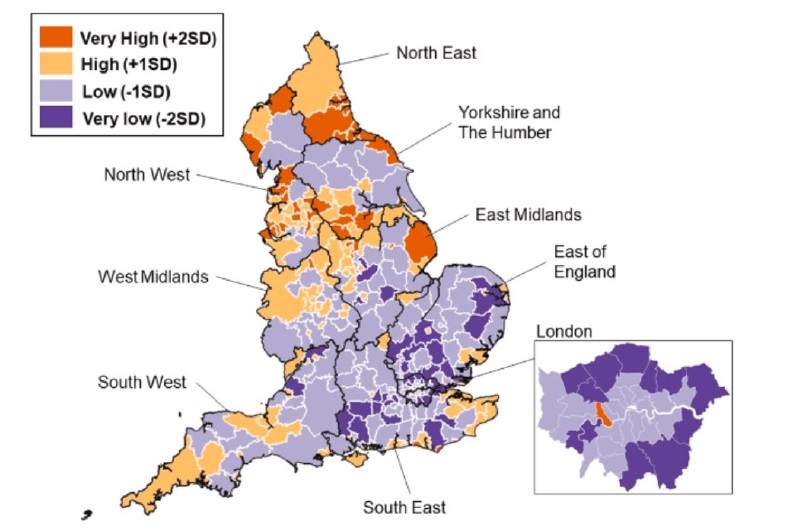

One very recent (February 2024) analysis of so-called “deaths of despair” (those related to alcohol use, drug use, or suicide) has highlighted the significant geographic differences in such deaths, and shows clearly the much higher rates in many parts of the North of England – including in Cumberland – as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13: Standardised rates of “deaths of despair” (relating to alcohol, drugs or suicide). Camacho et al (2024)

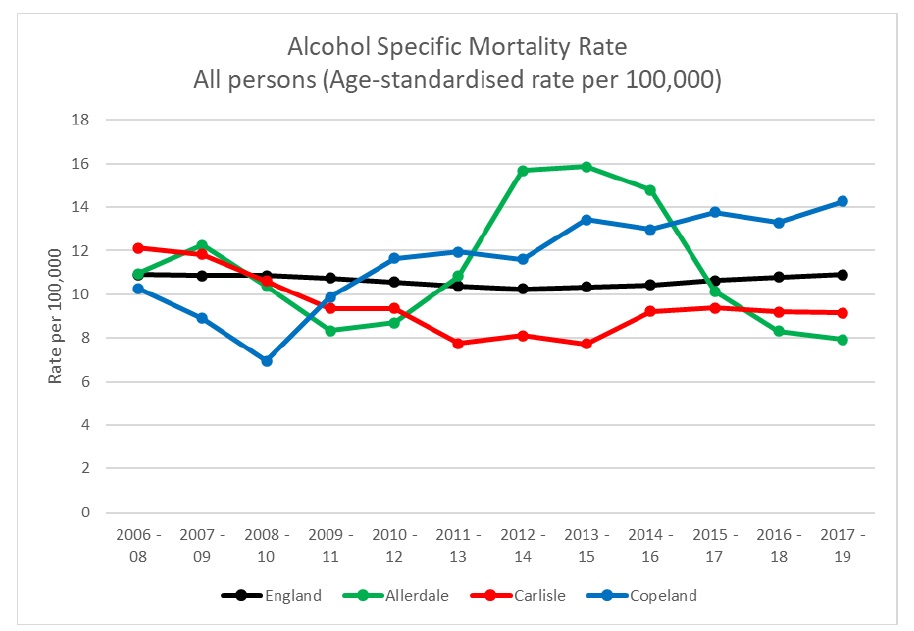

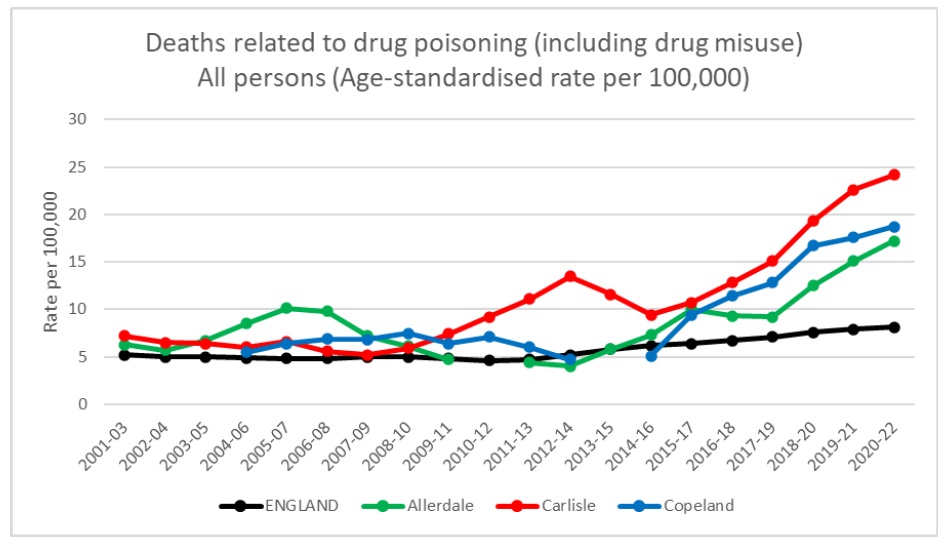

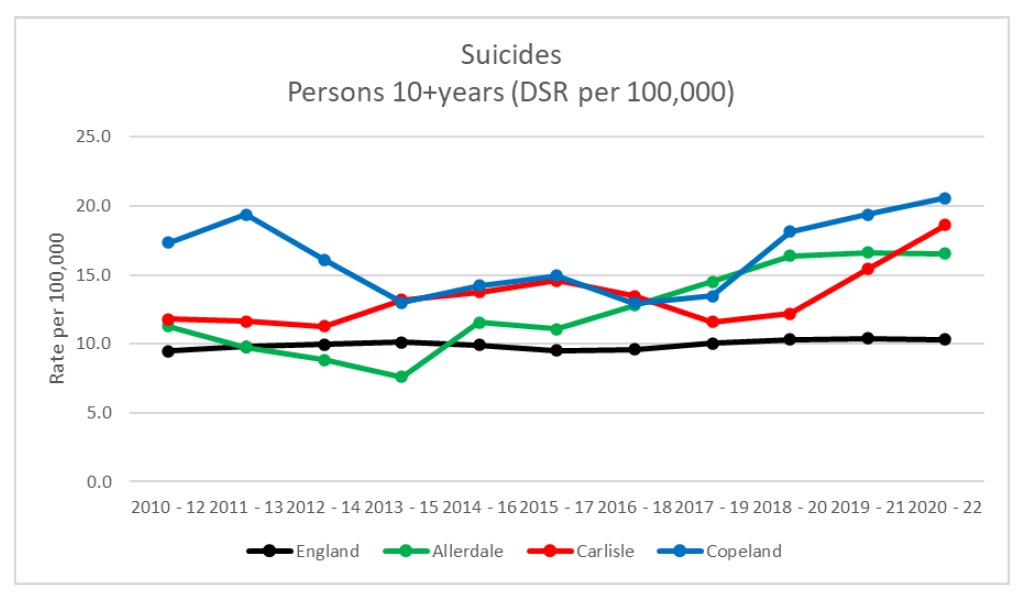

Looking at Cumberland in more detail, some very worrying recent trends can be seen. Our alcohol specific mortality data is somewhat out of date, with the most recent figures available being for 2017-19, but this shows rates below the England average in Allerdale and Carlisle, but higher in Copeland (Figure 14). Our drug-related deaths (Figure 15), and suicide rates (Figure 16), on the other hand, are rising rapidly and are substantially higher than the England average.

Figure 14: Alcohol specific mortality rates

Figure 15: Deaths due to drug poisoning (including drug misuse)

Figure 16: Suicide rates

Worryingly, more recent unpublished data indicates that our suicide rate has continued to climb substantially over the last two years.

Summary

However you look at it, it seems clear that mental health challenges in Cumberland are higher than the national average, and getting worse – or at least, demand for support, and the negative consequences of poor mental health, are increasing. And these challenges, like most other health concerns, are worse in our more deprived communities. The impacts of this are profound, both for human suffering and the ability of local services to respond; these rising rates of demand are simply unsustainable for our current services. Even if increased funding was available – which is extremely unlikely, at least to the extent that would be required – we would struggle to recruit the qualified staff to run our current service model. An alternative approach is desperately needed.