Trauma can be defined as an individual’s emotional, psychological, and physiological response to an overwhelming, distressing event or a series of events that exceed their ability to cope, leading to a profound disruption in their sense of safety, security, and well-being. This experience often challenges the individual’s ability to integrate and make sense of their emotions and perceptions, leaving a lasting impact on their mental, emotional, and physical health.

It is arguable that the word “trauma” has recently been over-used to the extent that it has become devalued as a descriptor, with even relatively low level adverse experiences sometimes being described as traumatic. It can be helpful to see trauma and adversity in four different categories:

- Event-based trauma: This encompasses single, discrete traumatic incidents, such as accidents, natural disasters, or acts of violence. These events are typically intense and acute, leading to an immediate stress response that may result in post-traumatic stress symptoms.

- Developmental trauma: Developmental trauma involves experiences of chronic stress or adverse events during critical periods of childhood development. These ongoing adverse experiences, such as poor attachment, neglect, abuse, or chronic instability, can significantly affect a child’s neurological, emotional, and social development, leading to long-term consequences in adulthood.

- Complex trauma: Complex trauma encompasses prolonged, repeated, and often interpersonal traumatic experiences, such as chronic abuse, neglect, or exposure to community violence. This form of trauma can result in multifaceted and enduring consequences, affecting various aspects of an individual’s functioning including their sense of self, relationships, emotional regulation, and cognitive processing.

- Continuous or low-level trauma (adversity): This category acknowledges long-term exposure to lower-level stressors or adverse conditions, such as ongoing discrimination, poverty, or environmental stressors. Although these experiences may not be characterised by acute trauma, their cumulative impact over time can lead to significant psychological distress and contribute to mental health difficulties.

These categories are of course not entirely independent of each other, and can layer up for some people. Poor childhood attachment may, for example, be connected to family poverty and domestic violence, and those experiences may in turn lead to someone experiencing a range of complex traumas as they grow up. Trauma can, sadly, breed further ongoing trauma. And different traumatic experiences can interact; someone may experience both poverty and (unrelated) discrimination as a result of having a marginalised minority characteristic.

While the importance of trauma is to some extent recognised in conventional biomedical approaches to mental health, being explicitly the trigger for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, for example, many theorists have argued that it is fundamental to many or most mental health conditions.

Trauma theory serves as a foundational framework for understanding the profound impact of traumatic experiences on an individual’s mental health and overall well-being. It describes how exposure to distressing, life-threatening, or overwhelmingly distressing events can significantly shape one’s psychological and emotional responses. The impact of trauma can manifest across various domains, and its effects often transcend singular diagnoses, contributing to a broad spectrum of mental health challenges. Key facets of trauma theory include:

- Types of trauma: As described above, traumatic experiences can encompass a wide array of events, including but not limited to physical or emotional abuse, neglect, natural disasters, accidents, combat exposure, loss of a loved one, or witnessing violence. The subjective nature of trauma implies that an event’s impact can vary significantly based on an individual’s perception and response.

- Disruption of safety and coping mechanisms: Trauma disrupts an individual’s fundamental sense of safety, stability, and control over their environment. It overwhelms an individual’s coping mechanisms, leaving a lasting impact on their emotional regulation, cognitive functioning, and interpersonal relationships.

- Post-traumatic stress responses: Traumatic experiences often lead to a range of posttraumatic stress responses, which can include intrusive memories, flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, negative alterations in mood and cognition, and alterations in arousal and reactivity.

- Complex trauma stress responses: In cases of prolonged or repeated traumatic experiences, known as complex trauma (such as in childhood abuse or neglect), the cumulative effect can result in complex post-traumatic stress responses. These responses often entail difficulties in emotional regulation, disturbances in self-concept, relational challenges, and disruptions in cognitive processes.

It is essential to recognise that traumatic experiences can influence mental health across diverse spectra and may not always neatly align with specific diagnostic categories. Trauma theory underscores the need for a comprehensive, trauma-informed approach to mental health care that prioritises understanding an individual’s history, experiences, and coping mechanisms to provide appropriate and effective support and treatment.

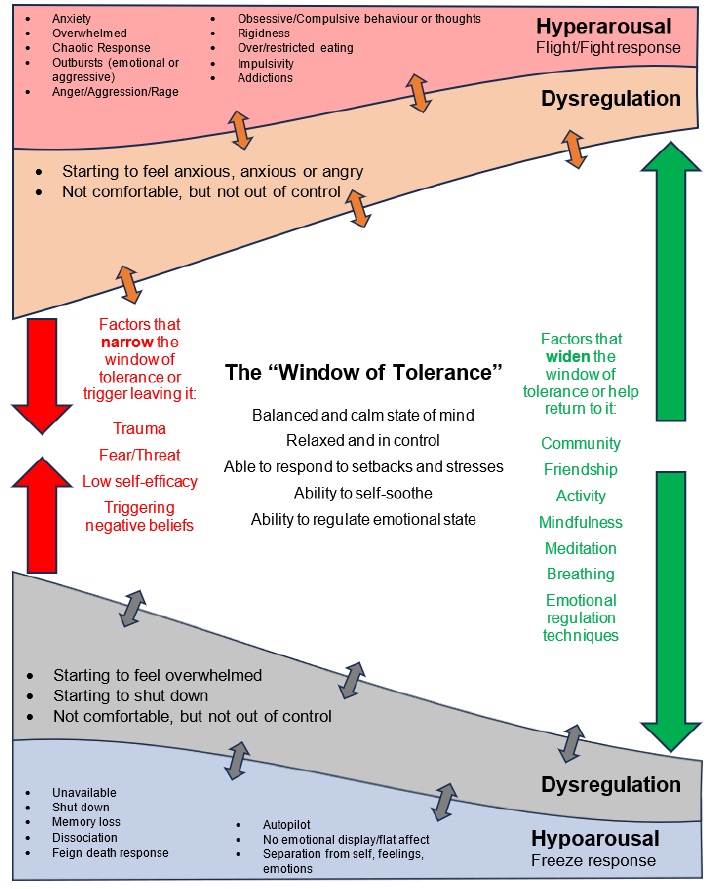

One helpful way of visualising the impact that trauma can have on mental health – and how people can be supported to cope with this – is with the “window of tolerance” model, illustrated in Figure 17. This recognises that people’s ability to remain emotionally wellregulated, or mentally healthy, can increase or decrease dependent on a wide range of external and internal factors and behaviours, and that moving outside of the space in which they are able to manage their own mental health can take the form of either hyper- or hypoarousal – ether a “fight or flight” response, or a “freeze” response.

Figure 17: The “Window of Tolerance” concept

Fundamentally, the symptoms of many conventional mental health diagnoses can be seen as either being characteristic of hyper- or hypo-arousal; given that the experience of trauma can significantly narrow someone’s “window of tolerance” this can arguably be a sufficient explanation for a wide range of traditional mental health diagnoses, including but not limited to:

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Characterized by persistent symptoms following exposure to a traumatic event, PTSD is often associated with re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in mood and cognition, and alterations in arousal and reactivity.

- Depression and anxiety disorders: Trauma can significantly contribute to the development or exacerbation of depressive and anxiety disorders, manifesting as persistent sadness, anxiety, panic attacks, or phobias.

- Substance use and addiction: Individuals may turn to a wide range of coping mechanisms to alleviate trauma-related distress, leading to substance use and/or other addiction issues including gambling, gaming and pornography addiction.

- Dissociative disorders: Severe trauma can lead to dissociative symptoms, where individuals may feel disconnected from their thoughts, emotions, or identity, such as in Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID).

- Personality disorders: While personality disorder is a highly contested concept even within traditional psychiatry, there is no doubt that trauma can contribute to symptoms and experiences that can result in diagnosis of personality disorders, particularly those linked to interpersonal and emotional dysregulation such as Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

It is important to note that not everyone who experiences trauma develops a psychiatric diagnosis or long-term mental health problems. Trauma can affect people in different ways, depending on a range of factors such as the nature, severity and duration of the trauma, the availability of support, the individual’s personality, coping skills and previous history of trauma. Some people may be able to overcome trauma with minimal or no professional intervention, especially if they have adequate protective factors and resources, such as supportive relationships, social networks, self care practices and positive beliefs. Some people may even experience post-traumatic growth, which refers to the positive psychological changes that can occur as a result of facing and coping with trauma. These changes can include increased appreciation of life, enhanced personal strength, improved relationships, greater spirituality and a recognition of new possibilities or opportunities. People who experience post-traumatic growth may develop considerable resilience, skills, insights and attributes that can be used to great effect in their personal and professional lives. This does not mean that they do not suffer or struggle, but rather that they are able to find meaning and value in their traumatic experiences and use them as a catalyst for positive change.

Implications for public mental health

The aim of a public mental health approach is to improve mental health and wellbeing at a population level. While treatment services can be part of this approach, it includes a key focus on preventing mental health problems from arising in the first place, and on putting protective measures in place to mitigate their effects when they do occur. The impact of trauma – particularly when extended into broader adversity – has clear implications for public mental health, which, like so many physical health problems, can be seen to be closely linked to poverty, discrimination and inequality. In addition, it becomes impossible to overstate the importance of childhood experience, which – even in the absence of acute trauma – is where a person’s way of interpreting the world is forged. A refreshed approach to public mental health in Cumberland would include:

- Tackling social and economic determinants: In the long term, of course, the aim is to prevent people from experiencing so much trauma in the first place. This is a significant societal challenge, given the variety of adverse experiences that people can have and the impact of wide social, economic and cultural factors. However a particular focus on tackling poverty, discrimination, domestic violence and substance misuse (which can cause trauma as well as being a symptom of it) is likely ultimately to have the biggest impact on people’s experience of trauma, and therefore on their long term mental health and wellbeing.

- Early intervention and support for children and families: Children and young people are particularly susceptible to the impact of trauma because it shapes their brain development and the way in which they interpret and interact with the world. A comprehensive programme of universal, early intervention, and children’s social care services aimed at developing secure attachment and supporting all families to bring children up in a stable and loving environment is crucial in building public mental health over the long term.

- Resilience training and education: While being brought up in a secure and loving environment is one important factor in developing resilience to life’s challenges, there are other ways in which this can be taught and practiced. Programmes such as Decider Skills – which uses the principles of cognitive behaviour therapy to teach people how to monitor and manage their own thoughts and emotions – can build valuable skills for preventing adversity from triggering mental health problems.

- Community engagement and collaboration: Many people with adverse experiences cope with them on their own or with the support of family, friends and peers – and many others could be helped to do so. Involvement of wider communities in recognising these issues and responding sensitively to diversity could help to create a network of support for individuals affected by trauma.

The Well Communities .

The Well Communities is a nationally renowned Lived Experience Recovery Organisation (LERO). While it formed around substance misuse, none of its members come with just one presenting problem – addiction, mental health, homelessness and criminal behaviour often go hand in hand, with past trauma being the common factor in most cases, and the approach is just as suited to mental health recovery where no addictions are present. The Well Communities uses the lived experience of its members to create a trauma safe environment that is focussed on connection (back to self and with the community), creating meaning and purpose and inspiring hope, enabling people to overcome and recover from their presenting issues.

The community-led LERO “reach one teach one” approach provides co-produced meaningful and purposeful mechanisms of support which place the client front and centre. Clear benefits are derived from the knowledge that the individual delivering the intervention has experienced the difficulties themselves and managed to regulate and overcome them. LEROs do not view discharge after shortterm treatment as a measure of success as they understand the relapsing nature of the condition, hence the intentional community led structure of such organisations.

“I believe that People Of Lived Experience give people that first glimmer of HOPE they need to overcome their presenting issues. I formulated the idea for a hub in the heart of the community, a lighthouse where visible recovery from trauma, addictions and mental illness was happening in the open, not hidden inside traditional services. I knew that addiction was contagious; if you hang around with people using drugs, you eventually do the same. I reasoned that recovery could be infectious too.”

Dave Higham, Founder, The Well communities

Box 2: Lived Experience Recovery Organisations

Implications for services and interventions

This recognition of the importance of trauma on people’s mental health and wellbeing has a number of important implications for how services function. These include:

- A shift to a trauma-informed approach: Mental health services in particular could shift from a diagnostic and treatment-focused approach to a trauma-informed model that prioritises understanding a person’s history and experiences. One such approach is the Power/Threat/Meaning Framework described in Box 3; adoption of such a model could be transformative for services and service users. More broadly, a wide range of services would benefit from becoming trauma-informed, shifting from asking “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?” This completely changes perceptions of what support might be appropriate.

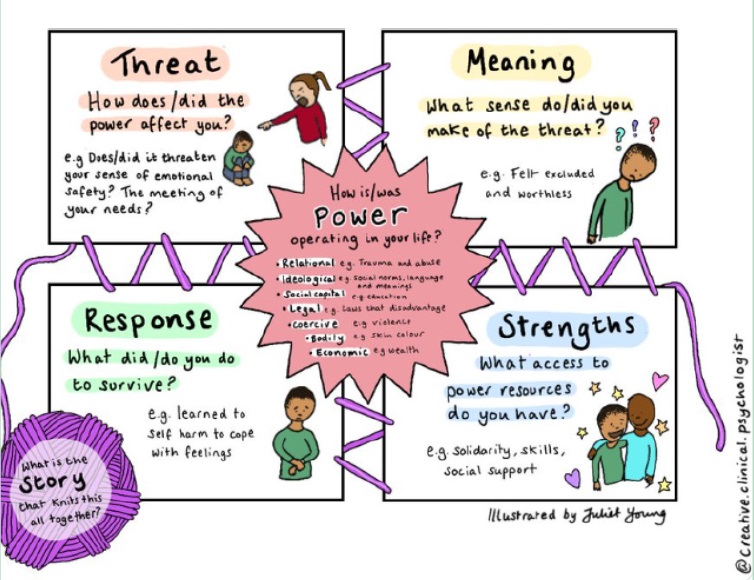

Box 3: The Power Threat Meaning Framework

The Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) is a conceptual framework that offers an alternative perspective to the traditional diagnostic model of mental health problems. Instead of focusing on symptoms and diagnoses, the PTMF explores how power imbalances, adverse experiences, and societal influences contribute to individuals’ distress and behaviour. It considers the impact of social, cultural, and environmental factors on mental health, emphasising the importance of understanding individuals’ experiences within broader contexts. The PTMF encourages a narrative-based approach, where individuals’ stories and meanings are central to understanding their distress, rather than applying diagnostic labels. It aims to empower individuals by validating their experiences, promoting self-understanding, and supporting meaningful pathways to recovery. Overall, the PTMF provides a comprehensive framework for understanding mental health difficulties that integrates psychological, social, and political perspectives.

- Increased access to trauma-specific services: Cumberland has a significant gap in services specifically skilled in helping people cope with trauma, both for children and adults. While more trauma-informed general services would help many people, specialist services are also needed in some cases.

- Emphasising resilience and coping models: A key insight of this model is that what people are dealing with is not necessarily an illness to be cured, but an experience to be overcome or coped with. Supporting people to develop their coping mechanisms can therefore help build resilience as a key aspect of recovery.

- Provision of training and education: Understanding the impact of trauma is critical for a very wide range of service providers. A comprehensive programme of training and education in trauma recognition and trauma-informed care is therefore needed to ensure that they understand the principles and how to implement them effectively.

- The importance of holistic support services: The things that people find supportive in coping with and overcoming trauma are very varied and individual. Holistic support services that focus on empowerment, safety, compassion and healing are crucial; these may or may not be explicitly part of mental health provision.

- Lived experience as support: The value of support provided by people with shared lived experience has been increasingly recognised in recent years, particularly in the field of substance misuse but applicable more widely. Cumberland is fortunate to be home to some exceptional Lived Experience Recovery Organisations (LEROs) and broadening support for these into mental health recovery could transform local services.

There is some excellent work already underway in Cumberland that aims to support this transition to trauma-informed services, both at individual organisation level and collaboratively, such as through the Trauma Informed Cumbria initiative (see Box 4), but this could be significantly accelerated to make a difference more quickly.

Trauma Informed Cumbria .

Trauma Informed Cumbria is a collaborative of local organisations aiming to create a movement of change amongst Cumbrian professionals, raising awareness of trauma and improving everyone’s response through partnership working and sharing best practice. Becoming trauma informed can have such a transformative impact on the lives of local people, enabling individuals to turn improve their mental and physical wellbeing, It can lead to higher levels of service user engagement, improved retention rates and better outcomes. By signing the Trauma Informed Cumbria pledge organisations are committed to:

- Working with others to put trauma-informed and responsive practice in place across Cumbrian services.

- Delivering services that are actively informed by people with lived experience of trauma.

- Recognising the central importance of relationships that offer collaboration, choice, empowerment, safety and trust as part of a trauma-informed approach.

- Responding in ways that prevent further harm, and that reduce barriers, so people affected by trauma have equal access to the services they need, when they need it, to support their own journey of recovery.

In Cumberland, Trauma Informed Cumbria is co-ordinated by Safety Net, a third sector recovery organisation. Professionals can contact them directly for more information at office@safetynetuk.org or check out the Trauma Informed Website for training and event information and to sign up to the pledge. https://www.traumainformedcumbria.org.uk/

Box 4: Trauma Informed Cumbria

Conclusion

The importance of the impact of trauma on mental health and wellbeing cannot be overestimated; it is arguably the key factor driving the majority of poor mental health. As such a comprehensive, trauma-informed approach is needed in mental health services and much more broadly. Preventing it is extremely challenging, but the good news is that there is significant potential for positive outcomes when individuals are supported in their journey of healing and recovery from trauma. Lots of work is already underway to move services in this direction, but this needs to be given a substantial boost to embed it rapidly throughout all relevant services.