This chapter considers data on patterns of some aspects of learning disability, neurodiversity and special educational needs across Cumberland. It does not attempt to cover all learning disability or special educational needs; the former includes several clearly organic brain conditions, and the latter includes these but also incorporates needs associated with physical or sensory disability. The focus of this chapter is therefore narrower, focusing on those areas where it is plausible that there is a more significant sociocultural dimension to the current situation: where, consistent with the earlier discussion about mental health, there is a risk that we are significantly over-medicalising the situation.

Estimates of the proportion of children who have some additional learning support need range from approximately 1% (those clinically diagnosed) to around 20% (based on lived experience). In Cumbria in 2022-23, 17.3% of pupils received some sort of Special Educational Needs support. The challenge is that current clinical diagnostic systems are designed and scaled to respond to the lower number, and there is no way in which they could realistically be expanded to meet the demand of the higher proportion (Ginns, 2024). This leaves many people desperate for support and unable to access it. An alternative approach is desperately needed.

Data on Special Educational Needs

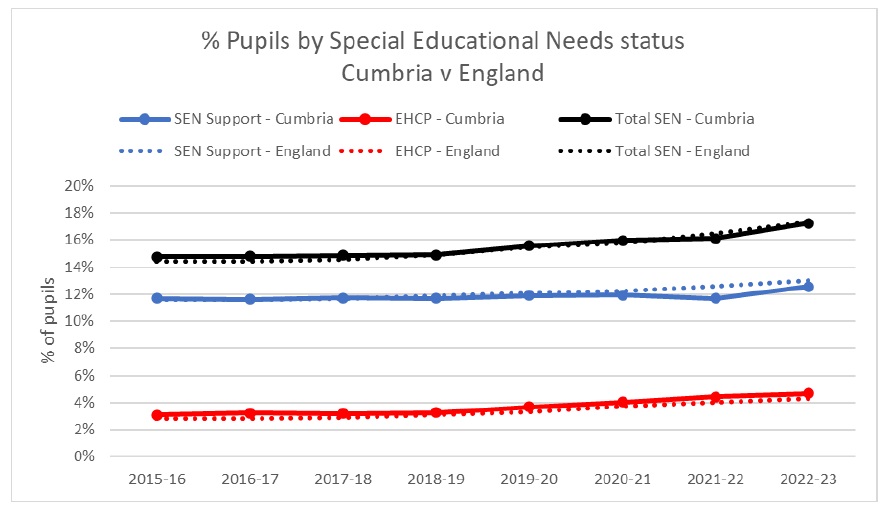

Data from the Cumbria Special Educational Needs Dashboard reveal some interesting patterns. Figure 18 shows that the number of children in receipt of some support for special educational needs is rising, and that Cumbria as a whole is effectively no different to the rest of the country.

Figure 18: Rate of special educational needs identified

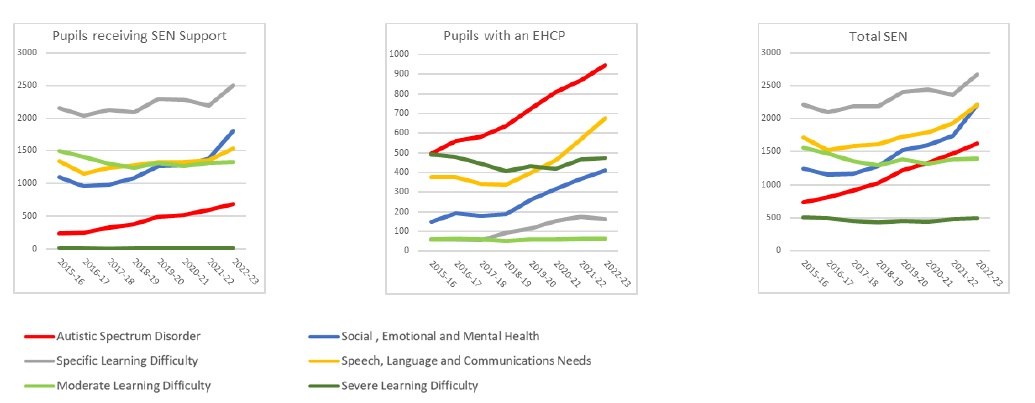

Drilling down into some particular categories of special educational need, as can be seen in Figure 19, the number of pupils identified as having a moderate or severe learning difficulty has remained broadly stable over recent years, as would be expected where conditions are predominantly neurodevelopmental. Specific learning difficulties (dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia) have risen substantially, by around 20% in total since 2015-16, as have speech, language and communication needs (by around 25%) – though here the dramatic difference is pupils receiving an EHCP. Autism spectrum disorders and social, emotional and mental health needs, on the other hand, have more than doubled. Such rising trends suggest changes that are socio-cultural rather than bio-medical. This does not mean that these special educational needs are “not real” – improved recognition of neurological differences is likely to be playing a role here, for example.

Figure 19: Numbers of pupils in Cumbria identified with particular Special Educational Needs

Secondary care data

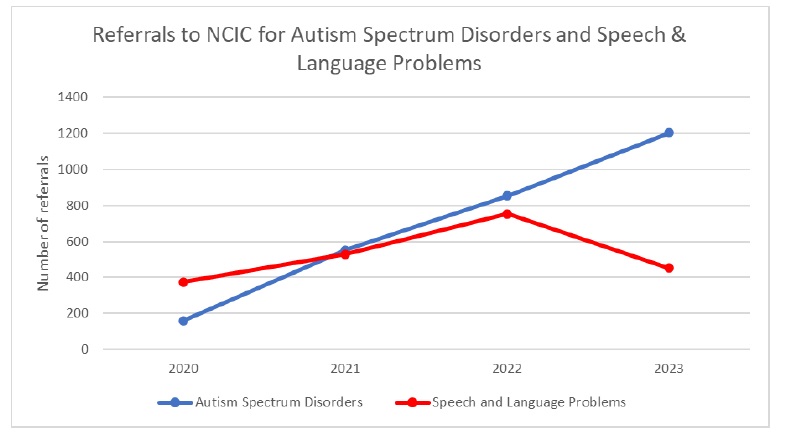

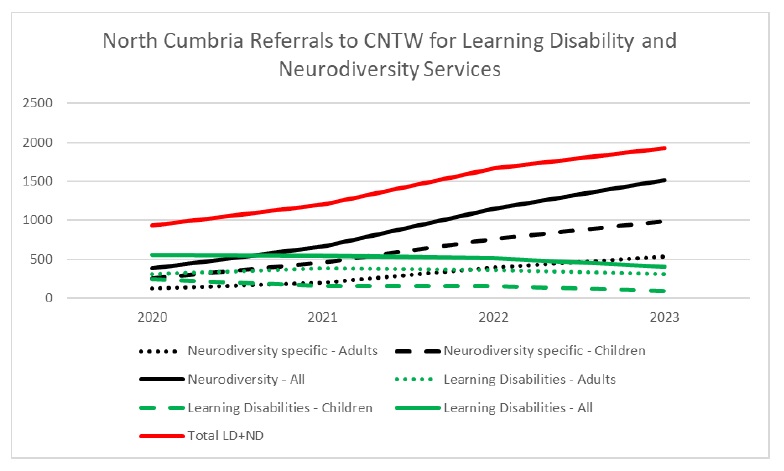

for clinical support. Figure 20 shows the change in referrals to North Cumbria Integrated Care paediatric services for Autism Spectrum Disorders and speech and language problems; while no clear trend is seen in the latter, the number of ASD referrals has increased six-fold in the last three years. The pattern in our specialist mental health services provided by Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne & Wear NHS Foundation Trust is slightly more complex (Figure 21): here referrals for learning disability have dropped slightly, while for neurodiversity the number has increased four-fold, with the two combined more than doubling in three years. This may reflect some of what was once referred to as learning disability being more recently described as neurodiversity; this may be a positive development, as described later in this report, but the fact of the rise in demand remains a challenge for services.

Figure 20: NCIC paediatric referrals for ASD and Speech & Language Disorders

Figure 21: North Cumbria referrals to CNTW for Learning Disability and Neurodiversity services

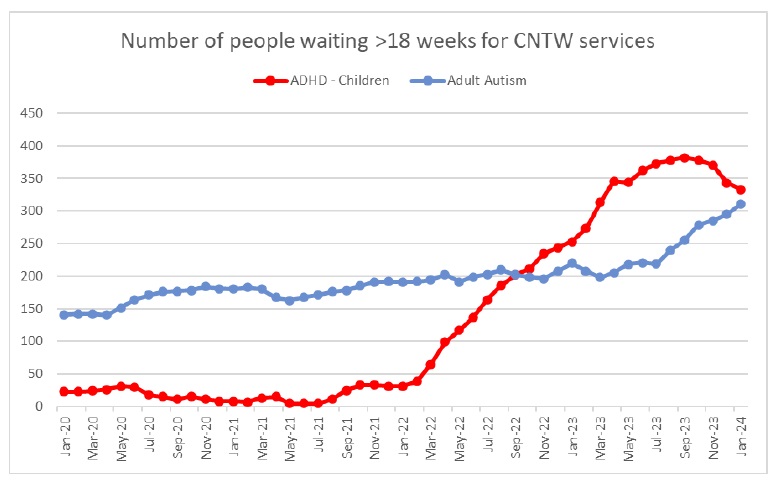

Needless to say, just as for mental health services this rise in demand has led to a rise in waiting times, as illustrated in Figure 22. Figures for ADHD in children are particularly startling, with numbers waiting for more than 18 weeks for services rising ten-fold in two years, but there is also pressure on adult focused services, with numbers waiting for adult autism services doubling in the last four years.

Figure 22: Increasing waiting times for key services

All these figures indicate a real rise in the number of people who feel that they (or their children) are struggling in some way. The key question, as with mental health, is what is causing this rise.

Understanding the rising demand

In conventional terms these rises are likely to be ascribed to two main factors:

- Changes in patterns of need: While the changes we are currently seeing are too rapid to be explained by things like genetic factors, there are social and environmental factors that could bring about a genuine shift in patterns of need, particularly in young children. The Covid-19 pandemic, for example, resulted in significantly reduced opportunities for social interaction; it is entirely plausible that infants who were not so widely exposed to other people at an important stage of their development could experience greater levels of social anxiety and challenges with speech and language as they get older and therefore to display behavioural patterns that overlap with autism. Foetal Alcohol Syndrome is another condition that can present as overlapping with autism or ADHD and may well be under-diagnosed as a result.

- Advancements in awareness and improvements in services: Even without real changes in patterns of need, increased awareness and understanding of neurodiverse conditions among both professionals and the general public could have played a significant role in driving demand for support services. As information about neurodiversity becomes more accessible, inclusive policies and legal protections for neurodiverse individuals get put in place, and healthcare and diagnostic services strive to respond to this growing awareness,so individuals and families are more likely to recognise and seek assistance for neurodiverse traits and challenges.

It is of course likely that these factors have played a part in the changing patterns of demand that we are seeing. However there are other, perhaps more challenging, explanations that also seem to be at play. These include:

- Changing social norms and expectations. There are considerable social pressures, particularly but by no means exclusively, on children and young people, to behave in particular ways and to be successful – as identified by conventional measures such as exam results and earning potential. There is therefore a motivation, both for individuals and for parents who want the best for their children, to try to “fix” any individual differences that could reduce such success, which leads to the medicalisation of these differences.

- Perception of diagnosis as a gateway to support. Linked to this is a sense that a diagnosis is a requirement in order to get support. Individuals and families may pursue diagnosis with the hope of accessing specialised therapies, educational accommodations, and community support networks tailored to their neurodiverse needs. As awareness of available resources grows, so too does the incentive to seek formal diagnosis and support. Sometimes this perception is accurate – for example in the case of disability-linked benefits – but at other times either there is in fact limited support even post-diagnosis, or support could in fact be available without such a formal categorisation.

- A search for meaning and explanation. For some people, a diagnosis can be a reassuring explanation for their (or their children’s) experiences or behaviour. In a society where parenting practices are often scrutinised, some parents may feel pressure to explain or mitigate their child’s differences to avoid judgment or criticism. Seeking a diagnosis and accessing appropriate support services can provide reassurance to parents, affirming that their child’s differences are not solely attributable to parenting choices but are instead part of their inherent neurodiversity. Likewise for adults who may have faced challenges throughout their lives, a diagnosis can offer a sense that these difficulties may have been caused by something almost external to themselves. For some people this may help reduce the responsibility they feel for their experiences and add to their sense of self understanding, which in turn helps improve their wellbeing.

Challenges to diagnosis-driven approaches

As in the field of mental health, for many years there have been critiques of biomedical approaches to learning disability. Emerging from the disability rights movement from the 1960s onwards, the social model of disability emphasised that societal barriers and norms often contribute more to people’s experience of disability than the inherent traits themselves do. To take an obvious example, someone who uses a wheelchair for mobility is “dis-abled” by split levels and steps; an environment with ramps and level access is enabling for that person, and while there is undoubtedly a very long way to go, society has made considerable progress in recognising this and putting measures in place to accommodate a wide range of physical and sensory challenges. A similar argument can be made for many learning difficulties: without conscious intervention, it is inevitable that society is designed around what works best for the “neurotypical” majority, leaving others potentially disadvantaged. If this can be overcome, however, strengths-based approaches recognise the unique strengths and abilities of neurodiverse individuals rather than pathologising their differences.

These alternative ways of looking at things, however valuable, often do not fundamentally challenge the centrality of diagnosis in categorising and identifying specific types of learning disability. As in mental health, however, there are some more fundamental challenges arising from this conventional approach. These include:

- Diagnostic Overreach: The diagnosis-centric model may lead to overdiagnosis, pathologising traits that may simply be natural variations in cognitive functioning. This tendency can contribute to medicalising normal aspects of human diversity.

- Stigmatisation: Focusing on diagnoses can perpetuate stigmatisation by reinforcing a binary distinction between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ cognitive functioning. Individuals with neurodivergent traits may experience social prejudices that can impact negatively on selfperception and acceptance.

- Individual Variability: A critical issue with diagnosis-driven approaches is their tendency to oversimplify complex neurodivergent experiences. Within a single diagnostic category, there exists significant individual variability in cognitive profiles, strengths, and challenges.

- Psychosocial Impacts: The psychosocial impacts of a diagnosis-centric model are far reaching. Individuals may experience lowered self-esteem, identity challenges, and heightened societal expectations, which can contribute to stress and mental health difficulties.

The neurodiversity paradigm: recognising cognitive diversity

The neurodiversity paradigm introduces a fundamental shift in our understanding of neurological variations. It emphasises that differences in neurological functioning, such as those associated with ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and other neurodivergent conditions, are not necessarily deviations or disorders; rather, they are integral aspects of the broader spectrum of human cognitive diversity. Key features of this model include:

- Natural Variability: Neurodiversity contends that the human brain is naturally diverse. Rather than adhering to a standardised model of cognitive functioning, it acknowledges the existence of a wide range of neurological variations.

- Cognitive Styles: In embracing a neurodiversity paradigm, conditions traditionally viewed as deficits or disorders are reframed as unique cognitive styles. For instance, ADHD might be seen as a cognitive style marked by high energy and creativity, while autism might be recognised as a cognitive style characterised by attention to detail and pattern recognition.

- Celebrating Diversity: Central to the neurodiversity paradigm is the celebration of cognitive diversity. It challenges the notion that a singular, ‘normal’ cognitive profile should be the benchmark, urging society to appreciate and value the richness that diverse cognitive styles bring to the human experience.

In summary, the neurodiversity paradigm challenges traditional views by recognising the inherent variability of human cognition and celebrating diverse cognitive styles. Simultaneously, it overcomes the limitations of diagnosis-driven approaches, urging a more nuanced and individualised understanding of neurodivergent experiences.

As things stand, however, society seems to be operating a strange mix of increasingly validating neurodiversity (and even celebrating it to an extent, with the contribution of neurodiverse people to a range of fields being recognised in popular culture, albeit sometimes in a somewhat stereotyped way), while simultaneously continuing to medicalise it and failing to respond to it in that nuanced and individualised way. In part this may be because there is an unfortunate cycle here: when society as a whole does not respond to neurodiversity in a nuanced way, it can present as highly challenging, disruptive behaviour that can be extremely difficult to manage on a day to day basis, particularly for parents and schools, which are trying to support everyone effectively and do not have the resources necessary to tailor their response appropriately. A society that truly embraced neurodiversity would better support 40 educators to identify individual learning styles and needs, without the need to diagnose and categorise people, and enable them to tailor education accordingly: this would include widespread availability of things like sensory-friendly classrooms, appropriate assistive technology, and personalised learning plans. It would celebrate different thinking styles in the workplace, make flexible working and what are currently seen as “reasonable adjustments” standard practice available to all, and provide wider opportunities for neurodiverse thinking styles to be recognised and rewarded as valuable talents. And it would ensure that health and care systems were responsive to a wide range of needs, with broad understanding of neurodiversity needs and support and information available in multiple formats.

Improving services (and society) for neurodiverse people

Becoming a society that recognises and celebrates cognitive diversity as normal will take time and effort. Much of the work is likely to have to take place in schools, to set the culture and approaches at an early stage; our workplaces are the other key setting for establishing a change in culture. The sort of action required includes:

- Mainstreaming strengths-based approaches: Educational settings and workplaces could use strengths-based assessments that focus on identifying and utilising the strengths and talents of neurodiverse individuals rather than solely identifying deficits. Training on recognising and supporting diverse styles could support this.

- Universal design for learning (UDL): UDL principles aim to ensure that teaching methods, materials, and assessments are accessible and cater to diverse learning needs without the need for specific diagnoses.

- Early intervention and support: Development of early intervention and support programs that are accessible to all students, irrespective of diagnostic labels. These programs can offer tailored assistance based on individual needs and strengths.

- Promoting inclusive cultures: Promoting inclusive school and workplace cultures that celebrate diversity, foster empathy, and reduce stigma associated with neurodiverse traits. Peer support programs and awareness campaigns can help to promote understanding and acceptance.

Some excellent practice already exists in Cumberland and beyond: the Portsmouth ND model, for example (see Box 5) shows considerable promise in helping to transform support for neurodiverse children and young people. A co-ordinated and systematic approach to improving services and changing culture is needed.

Portsmouth ND Model .

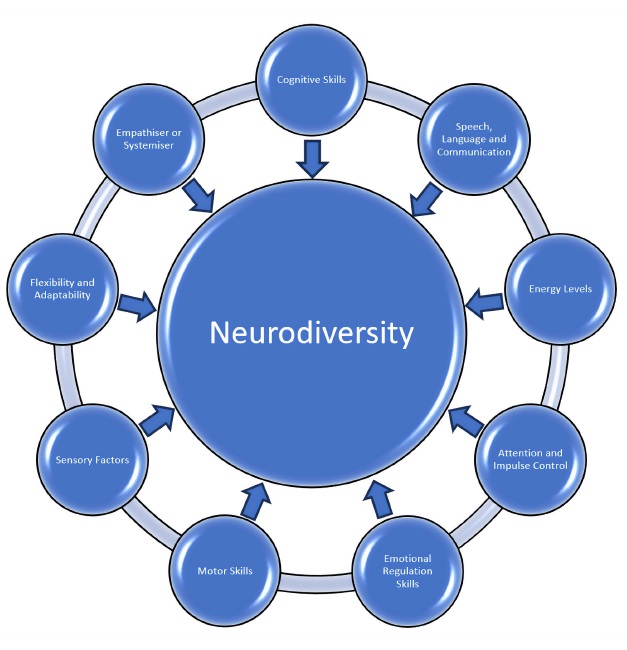

In 2019, Portsmouth was experiencing exactly the same sort of challenges that we currently face in Cumberland: long waiting times for diagnosis, with limited support afterwards, very frustrated and distressed families, and many children not getting the support they needed. Working with families they designed a new approach, including a neurodiversity profiling tool, based around nine domains, which can be used by a wide range of professionals to identify strengths, skills and areas of challenge that can then be responded to directly without waiting for a formal diagnosis.

Since implementing the model, early indications are that demand for diagnostic services has reduced by 89% and that children and families are receiving support much more quickly. Initial work has begun to plan implementing this approach in Cumberland.

Box 5: The Portsmouth ND Model

Conclusion

The culture around neurodiversity has been changing for the better in recent years. More people understand and accept that different brains work differently, and that this is not something to be ashamed of. But many parts of society still lag behind this change, and this creates a lot of frustration and difficulty for people who need support. The current systems of healthcare and education, especially, are not able to meet the demand or address the problems that people face. Many people have to wait a long time for diagnoses that, when they come, don’t actually help them much. But there are also some great opportunities to rethink our current ways of doing things and to try to make services and society in general more aware and respectful of neurodiversity.

A society that truly appreciated neurodiversity would make sure that everyone had equal opportunities, access, and inclusion in all areas of life, and that the unique talents and views of neurodiverse people were valued and celebrated. By seeing neurodiversity as a natural part of human diversity and focusing on strengths and individualised support, rather than treating it as a problem that needs to be fixed or cured, society would create a more compassionate and supportive environment for everyone.